First Visit

2016

Case presentation & history

Case presentation

Case history

Case history

Clinical examination

Clinical examination

T2DM: Type 2 diabetes mellitus; TID: Three times a day; HR: Heart rate; bpm: Beats per minute;

BMI: Body mass index; WHO: World Health Organization

Go to section:

Based on the clinical history, presenting symptoms,

and examination, what is your diagnostic orientation?

Metformin-induced hypoglycemia

Metformin-induced hypoglycemia is rare.1 Although bilateral

asterixis may occur in patients with hypoglycemia, typical

manifestations of hypoglycemia such as anxiety, profuse sweating,

shakiness, or tachycardia2,3 were lacking. Excluding drug-induced

cases and cases associated with severe hypokalemia, bilateral

asterixis is usually present in patients with hepatic

encephalopathy, uremia, or respiratory failure. Thus, other

diagnoses are more likely.

Diabetic ketoacidosis

The patient did not present with excessive thirst, polyuria,

vomiting, or polypnea that represent the common manifestations

of diabetic ketoacidosis.4 In contrast, bilateral asterixis is not

associated with either diabetic ketoacidosis or hyperosmolar

hyperglycemic syndrome.2,3 Therefore, the suggested diagnosis

is unlikely.

Hepatic encephalopathy

Right answer!

The patient’s clinical history (diabetes mellitus, obesity, and past

arterial hypertension) may suggest that lethargy and

disorientation for time were due to chronic vascular

encephalopathy. However, bilateral asterixis is not a sign of this

condition.2,3

Hepatic encephalopathy is among the events marking the

decompensation of cirrhosis, even though it is not the most

frequent.5,6 Due to diabetes mellitus and long-standing obesity,

it seems likely that the patient had chronic liver disease due to

non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), which can be associated

with brain dysfunction even before the establishment of

cirrhosis.7

Furthermore, the spontaneous resolution of arterial

hypertension is another finding suggesting the development of

chronic liver disease. Thus, the clinical context would justify the

presumptive diagnosis of overt hepatic encephalopathy.

Chronic vascular encephalopathy

The patient’s clinical history (diabetes mellitus, obesity, and past

arterial hypertension) may suggest that lethargy and disorientation

for time were due to chronic vascular encephalopathy. However,

bilateral asterixis is not a sign of this condition.2,3 Rather, chronic

vascular encephalopathy may be seen as a substrate favoring the

development of neurological symptoms due to metabolic

disturbances.8 Thus, another presumptive diagnosis is more likely.

Go to section:

Would you like to know about any additional information

to ascertain the diagnosis of hepatic encephalopathy?

Venous ammonia concentration

There is no close relationship between peripheral venous

ammonia concentration and the severity of hepatic

encephalopathy.5 Determination of ammonia concentration in the

arterial blood does not overcome this pitfall. However, although

the finding of normal ammonia levels does not necessarily rule out

the diagnosis of overt hepatic encephalopathy, normal ammonia

concentration should prompt for an alternative diagnosis,

especially when different diagnoses are likely.5,9 Thus, venous

ammonia concentration should be determined in this case, but

other investigations are also needed. The detected venous

ammonia concentration was 92 µmol/L (normal range: 6–47

µmol/L).

Neuroimaging

Neuroimaging should be performed when the diagnosis of overt

hepatic encephalopathy is suspected for the first time and,

sometimes, even in patients known to suffer from this

complication of cirrhosis.5,9 This is especially true in patients

presenting with potential alternative causes for their neurological

symptoms. In this patient, a brain scan excluded the presence of

focal lesions and reported initial signs of chronic vascular

encephalopathy. In addition to neuroimaging, other investigations

are needed.

Abdominal ultrasonography

Abdominal ultrasonography is relevant in this case, as it can

provide information related to the suspected liver disease, the

presence of portal hypertension, and the presence of other

complications such as ascites.10 Indeed, ultrasonography led to the

diagnosis of cirrhosis with portal hypertension. Moreover, it

revealed a spontaneous venous splenorenal shunt that likely was

the main cause of overt hepatic encephalopathy. However, in

addition to abdominal ultrasonography, other investigations are

needed.

All the above

Right answer!

There is no close relationship between peripheral venous ammonia concentration and the severity of hepatic encephalopathy.5 Determination of ammonia concentration in the arterial blood does not overcome this pitfall. However, although the finding of normal ammonia levels does not necessarily rule out the diagnosis of overt hepatic encephalopathy,5 normal ammonia concentration should prompt for an alternative diagnosis, especially when different diagnoses are likely.9 Thus, venous ammonia concentration should be determined in this case. The detected value was 92 µmol/L (normal range: 6–47 µmol/L).

Neuroimaging should be performed when the diagnosis of overt hepatic encephalopathy is suspected for the first time and, sometimes, even in patients known to suffer from this complication of cirrhosis.5,9 This is especially true in patients presenting with potential alternative causes for their neurological symptoms. In this patient, a brain scan excluded the presence of focal lesions and reported initial signs of chronic vascular encephalopathy.

Abdominal ultrasonography is relevant in this case, as it can provide information related to the suspected liver disease, the presence of portal hypertension, and the presence of other complications such as ascites.10 Indeed, ultrasonography led to the diagnosis of cirrhosis with portal hypertension. Moreover, it revealed a spontaneous venous splenorenal shunt that likely was the main cause of overt hepatic encephalopathy.

None of the above

All the suggested investigations from 1 to 3 are needed to ascertain the diagnosis of hepatic encephalopathy in this case.

There is no close relationship between peripheral venous ammonia concentration and the severity of hepatic encephalopathy.5 Determination of ammonia concentration in the arterial blood does not overcome this pitfall. However, although the finding of normal ammonia levels does not necessarily rule out the diagnosis of overt hepatic encephalopathy,5 normal ammonia concentration should prompt for an alternative diagnosis, especially when different diagnoses are likely.9 Thus, venous ammonia concentration should be determined in this case. The detected value was 92 µmol/L (normal range: 6–47 µmol/L).

Neuroimaging should be performed when the diagnosis of overt hepatic encephalopathy is suspected for the first time and, sometimes, even in patients known to suffer from this complication of cirrhosis.5,9 This is especially true in patients presenting with potential alternative causes for their neurological symptoms. In this patient, a brain scan excluded the presence of focal lesions and reported initial signs of chronic vascular encephalopathy.

Abdominal ultrasonography is relevant in this case, as it can provide information related to the suspected liver disease, the presence of portal hypertension, and the presence of other complications such as ascites.10 Indeed, ultrasonography led to the diagnosis of cirrhosis with portal hypertension. Moreover, it revealed a spontaneous venous splenorenal shunt that likely was the main cause of overt hepatic encephalopathy.

Go to section:

First Visit

2016

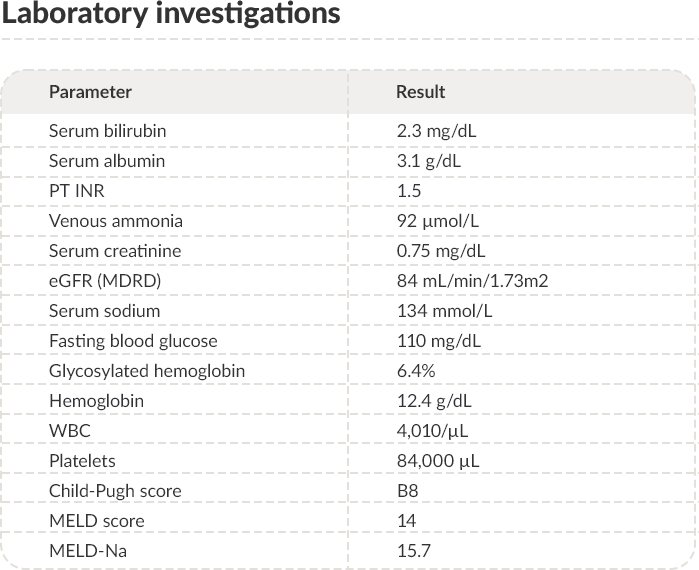

Imaging & laboratory investigations

PT: Prothrombin time; INR: International normalized ratio; eGFR: Estimated glomerular filtration rate; MDRD: Modification of diet in renal disease;

WBC: White blood cells; MELD: Model for end-stage liver disease; US: Ultrasound.

Go to section:

First Visit

2016

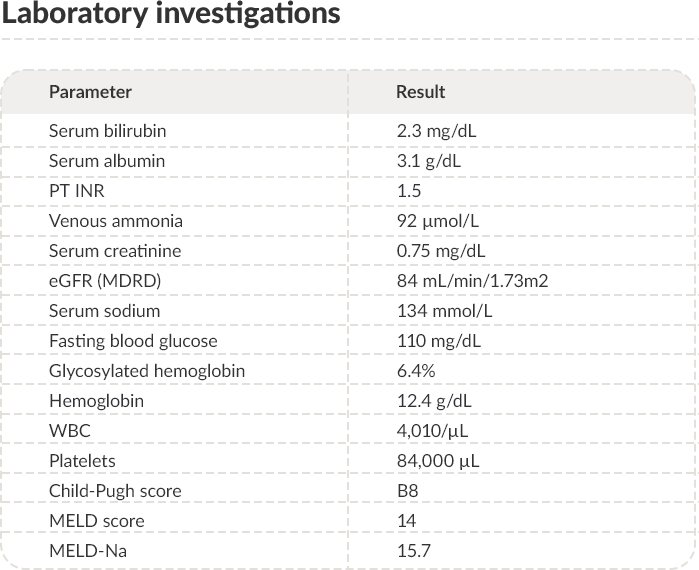

Diagnosis & management

NASH: Non-alcoholic steatohepatitis; b.i.d.: Twice a day; t.i.d.: Three times a day.

Go to section:

Second Visit

SEP2018

SECOND presentation, investigations & diagnosis

Case presentation

Case history

Investigations

Clinical examination

Diagnosis

GI: Gastrointestinal.

Go to section:

Go to section:

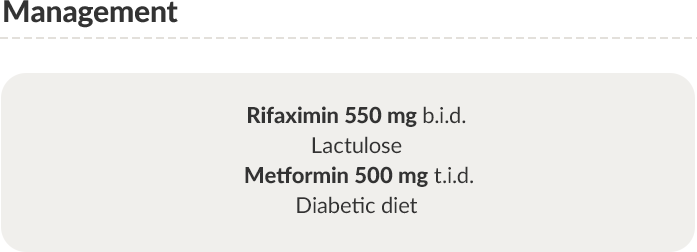

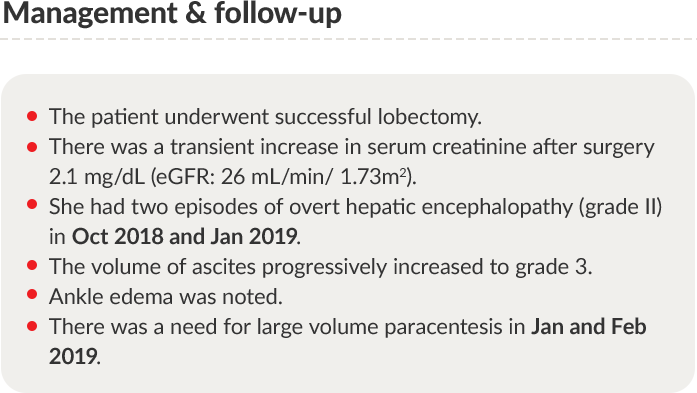

OCT 2018-

FEB2019

Management & follow-up

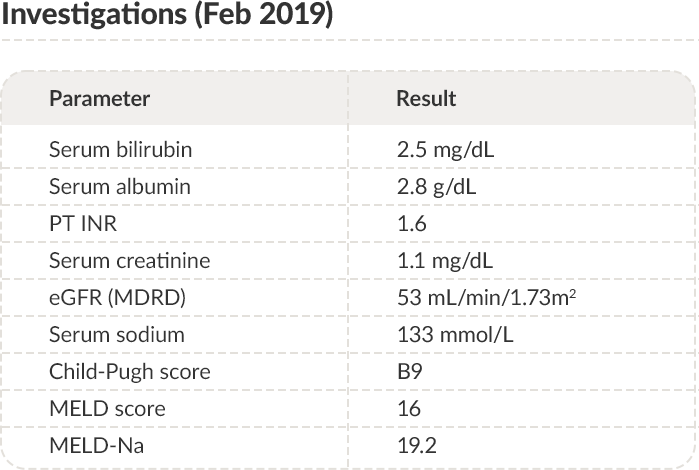

PT: Prothrombin time; INR: International normalized ratio; eGFR: Estimated glomerular filtration rate; MDRD: Modification of diet in renal disease;

MELD: Model for end-stage liver disease.

Trends in serum albumin

Go to section:

Trends in serum albumin

NASH: Non-alcoholic steatohepatitis; HE: Hepatic encephalopathy

Go to section:

How would you prevent paracentesis-induced

circulatory dysfunction?

Human albumin 20%, 4 g/L of tapped ascites

Current guidelines recommend infusing human albumin to prevent paracentesis-induced circulatory dysfunction (PICD) and its complications.11-13 Clinical trials and metanalyses showed that albumin is superior to other plasma expanders or vasoconstrictors. When 5 or more liters of ascites are removed, the usual recommended albumin dose consists of 8 grams per liter of ascites.11-13 Some studies have suggested that lower albumin doses (4 g/L of ascites) may be equally effective.11 However, these trials were underpowered to warrant equivalence.

Whether the removal of fewer than 5 liters of ascites requires the same treatment remains undefined. However, in the absence of evidence-based alternatives and considering that artificial plasma expanders may induce severe allergic reactions and can endanger renal function, the use of albumin is considered prudential.14

Human albumin 20%, 8 g/L of tapped ascites

Right answer!

This answer is correct. Indeed, current guidelines recommend infusing 8 g of human albumin per liter of ascites when 5 or more liters of ascites are removed.11-13 Clinical trials and metanalyses have shown that albumin is superior to other plasma expanders or vasoconstrictors.11,13 Some studies suggested that lower albumin doses (4 g/L of ascites) may be equally effective.11 However, these trials were underpowered to warrant equivalence.

Whether the removal of fewer than 5 liters of ascites requires the same treatment remains undefined. However, in the absence of evidence-based alternatives and considering that artificial plasma expanders may induce severe allergic reactions and can endanger renal function, the use of albumin is considered prudential.14

Prevention not needed

Paracentesis-induced circulatory dysfunction (PICD) is a frequent complication of large-volume paracentesis. It is due to splanchnic arterial vasodilation leading to a fast reduction of effective blood volume.15 Renal failure, dilutional hyponatremia, hepatic encephalopathy and even death can follow PICD.16 Therefore, its prophylaxis is warranted.

Based on the emerging evidence from clinical trials and meta-analyses, current guidelines recommend the administration of 8 g of human albumin per liter of ascites when 5 or more liters are removed.11-13 Prophylaxis of PICD is also indicated when less than 5 liters of ascites are removed, even though it remains undefined whether this setting also requires the same treatment. However, in the absence of evidence-based alternatives and considering that artificial plasma expanders may induce severe allergic reactions and can endanger renal function, the use of albumin is considered prudential.14

Dextran 70, 8 g/L of tapped ascites

The use of Dextran 70, along with other colloids, to prevent paracentesis-induced circulatory dysfunction (PICD) has been assessed by controlled clinical trials.13,16 Although Dextran reduced the incidence of complications, its efficacy is lower than human albumin when 5 or more liters of ascites are removed.11,13,16 Therefore, current guidelines recommend preventing PICD by infusing 8 g of human albumin at the end of paracentesis.11-13 It should not be disregarded that synthetic colloids are potentially associated with side-effects such as anaphylaxis, coagulopathy, or renal failure.13,17-19

Go to section:

END MAR

2019

THIRD presentation & investigations

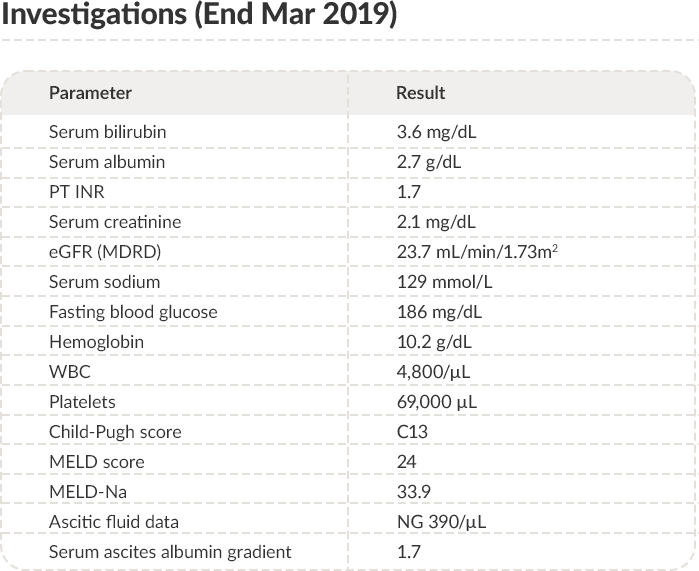

PT: Prothrombin time; INR: International normalized ratio; eGFR: Estimated glomerular filtration rate; MDRD:

Modification of diet in renal disease; WBC: White blood cells; MELD: Model for end-stage liver disease.

Trends in serum albumin

Go to section:

Trends in serum albumin

NASH: Non-alcoholic steatohepatitis; HE: Hepatic encephalopathy

Go to section:

What would be your first diagnosis?

Poor treatment compliance

In patients with cirrhosis on diuretic treatment and increasing episodes of ascites, poor compliance to drugs or diet must be considered. However, concomitant signs and symptoms, such as overt hepatic encephalopathy, constipation, and low-grade fever could not be explained. Therefore, an alternative answer would be more appropriate.

Severe hyperglycemia

Urinary volume contraction conflicts with severe hyperglycemia, which should favor osmotic diuresis. Moreover, hyperglycemia would not justify the presence of low-grade fever. A search for a common cause of all symptoms and signs would be warranted.

Spontaneous bacterial peritonitis

Right answer!

Spontaneous bacterial peritonitis (SBP) is among the most frequent bacterial infections in patients with cirrhosis and ascites.20,21 Untreated SBP is associated with an ominous prognosis and, therefore, early diagnosis is essential.22 It must be recalled that, in its initial phase, the infection involves the ascitic fluid but does not extend to the peritoneum.21 Therefore, peritonism only appears in the late stages of the disease when the risk for mortality despite correct treatment becomes very high. The early symptoms presented by patients with SBP are often non-specific, such as low fever, moderate abdominal pain, mild tenderness, and slowed peristalsis.20 The suspicion should then arise when the overall patient's clinical condition worsens without an apparent cause. The development of overt hepatic encephalopathy, jaundice, poor response to diuretics, or frank oliguria should always lead to the suspicion of SBP.20

Dietary protein overload

Dietary protein overload is a well-known cause of overt hepatic encephalopathy. However, protein overload alone does not explain the other signs and symptoms presented by the patient at hospitalization.

Go to section:

How would you manage spontaneous bacterial

peritonitis in this case?

Piperacillin-tazobactam

Third generation cephalosporins, such as cefotaxime or ceftriaxone, or amoxicillin/clavulanic acid are traditionally employed to treat spontaneous bacterial peritonitis (SBP). These approaches are associated with high resolution rates of the infection, especially when treatment is initiated in the early phase of SBP.12,23-25 However, the spread of beta-lactamase-producing microorganisms makes these treatments unsuitable in many conditions, including community-acquired infections.23-25 Therefore, piperacillin-tazobactam may be preferred, especially in patients with past courses of antibiotic therapy, frequent admissions to the hospital, history of invasive procedures, or history of healthcare associated or nosocomial infections.12,13, 23,25

It must be recalled that antibiotic treatment should be combined with human albumin infusion as prophylaxis of SBP-induced acute kidney injury, which is major cause of mortality in this context.13

Third-generation fluoroquinolone

Third-generation fluoroquinolones are mostly used for primary and secondary prophylaxis of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis (SBP).13,25 The worldwide spread of microorganisms resistant to fluoroquinolones makes these antibiotics scarcely suitable to treat SBP, especially in patients with past courses of antibiotic therapy, frequent admissions to the hospital, history of invasive procedures, or history of healthcare associated or nosocomial infections. Thus, an alternative is advisable.12

Third-generation cephalosporin

Third-generation cephalosporins are traditionally employed in the treatment of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis (SBP) ensuring high resolution rates of the infection, especially when treatment is initiated in the early phase of SBP.12,25 However, the spread of beta-lactamase-producing microorganisms makes this treatment unsuitable in many conditions, including community-acquired infections.25 Therefore, piperacillin-tazobactam is preferable especially in patients with past courses of antibiotic therapy, frequent admissions to the hospital, history of invasive procedures, or history of healthcare associated or nosocomial infections.13,25

Piperacillin-tazobactam

+ human albumin prophylaxis

Right answer!

The spread of beta-lactamase-producing microorganisms makes the traditional treatments such as third generation cephalosporins (cefotaxime or ceftriaxone), or amoxicillin/clavulanic acid unsuitable in many conditions, including community-acquired infections.23-25 Therefore, piperacillin-tazobactam may be preferred, especially in patients with past courses of antibiotic therapy, frequent admissions to the hospital, history of invasive procedures, or history of healthcare associated or nosocomial infections 12,13,23,25

Acute kidney injury (AKI), either hepatorenal syndrome or acute tubular necrosis, is a relevant cause of mortality in patients with cirrhosis and spontaneous bacterial peritonitis (SBP).25 Current guidelines recommend addition of albumin therapy (1 g/Kg b.w. at diagnosis, and 1 g/Kg b.w. on day 3) to antibiotics to prevent this complication.13,26 A controlled clinical trial showed that albumin prophylaxis lowers the occurrence of AKI and in-hospital and 3-month mortality.26

Therefore, antibiotic treatment should be combined with human albumin infusion as prophylaxis of SBP-induced acute kidney injury, which is major cause of mortality in this context.12,13 Whether or not this prophylactic treatment should also be employed in patients at low risk of developing AKI, as defined by serum bilirubin concentration <4 mg/dL or serum creatinine concentration <1 mg/dL, is still not defined.12

Go to section:

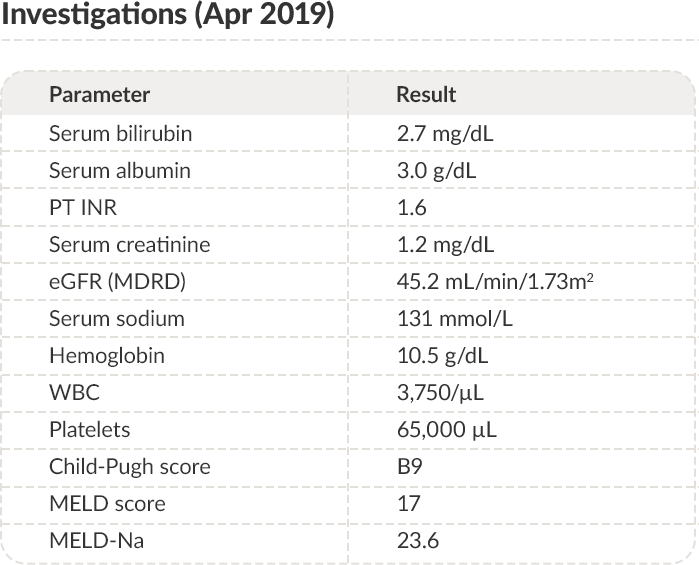

APRIL

2019

FOURTH presentation & investigations

PT: Prothrombin time; INR: International normalized ratio; eGFR: Estimated glomerular filtration rate; MDRD:

Modification of diet in renal disease; WBC: White blood cells; MELD: Model for end-stage liver disease

Trends in serum albumin

Go to section:

Trends in serum albumin

NASH: Non-alcoholic steatohepatitis; HE: Hepatic encephalopathy

Go to section:

How would you manage this patient?

Stop diuretics

The patient did not meet the criteria for diagnosing refractory ascites.12,13,27 Even though large-volume paracentesis was occasionally necessary, the patient was still responding to diuretics. Glomerular filtration rate and serum sodium concentration were reduced, but the extent of these abnormalities did not prevent the use of diuretics. Therefore, an adjustment of diuretic dosage, but not their withdrawal, could be considered.

Increase diuretic dosage

Based on the current guidelines, the dosage of diuretics (both spironolactone and furosemide) could be increased. Indeed, both dosages were still lower than the recommended maximal doses (spironolactone 400 mg/day and furosemide 160 mg/day).12,13 However, glomerular filtration rate and serum sodium concentration were reduced, and the patient presented with fluctuating hepatic encephalopathy. Therefore, the risk of developing diuretic-induced side effects was high. An alternative therapeutic strategy could be considered.

Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic

shunt (TIPS) insertion

Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS) insertion is potentially indicated in patients with recurrent or refractory ascites.28 Therefore, it could be considered in this case. However, the patient presented with persistent overt hepatic encephalopathy, which represents a contraindication to TIPS.28 Even though the use of polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE)-covered stents of small caliber (8 mm) reduces the incidence of TIPS-related hepatic encephalopathy, it does not efface the risk for this complication completely.12,29 Moreover, 8 mm stents may not be sufficient to ensure a beneficial effect on ascites.13 Therefore, the choice of inserting TIPS in this patient may not be appropriate.

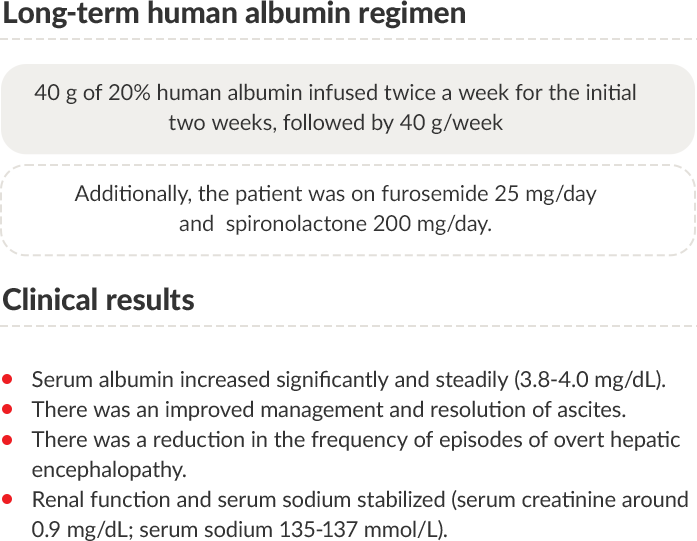

Long-term human albumin administration

Right answer!

The ANSWER trial, published in 2018, compared the effects of standard medical treatment versus long-term human albumin administration in patients with cirrhosis and uncomplicated ascites needing diuretic therapy–30

For these reasons, long-term albumin administration may be a rational choice in this case.

Go to section:

What is the rationale underlying long-term human

albumin administration in patients with cirrhosis and

uncomplicated ascites?

Increase plasma colloid osmotic

pressure

Albumin is the most abundant circulating protein accounting for almost 80% of plasma colloid osmotic pressure.31 A common belief is that hypoalbuminemia disrupts Starling forces equilibrium, facilitating ascites formation. However, we should recall that the net transcapillary fluid exchange results from the hydrostatic and oncotic pressure gradients rather than their absolute values.32 Post-sinusoidal portal hypertension increases intravascular hydrostatic pressure enhancing the fluid flow towards the interstitium, where the drainage by the lymphatic system maintains a lower pressure.32 In contrast, albumin concentrations and, therefore, colloid osmotic pressures decline in parallel in both compartments.32,33 Thus, reduced albumin concentration does not play a pre-eminent role in ascites formation and should not represent, per se, a reason for albumin administration in cirrhosis.

Take advantage of albumin non-oncotic

properties

Right answer!

Besides its oncotic power, albumin possesses functional domains with relevant properties, such as the free cysteine residue in position 34, which exerts potent anti-oxidant and scavenging activities, the amino-terminal that binds and removes highly toxic reactive metal species, and other domains binding a variety of endogenous and exogenous substances.34,35 Moreover, albumin has immune-modulatory functions, protects capillary integrity, and influences acid-base balance and coagulation. These properties assume relevance in patients with advanced cirrhosis.34 Indeed, advanced cirrhosis is characterized by a pro-inflammatory and pro-oxidant milieu deriving from immune cell activation induced by an abnormal intestinal translocation of bacteria and bacterial products.36 Moreover, besides the well-known quantitative reduction of circulating albumin, it has become clear that serum albumin in cirrhosis undergoes functional and structural changes that endanger its non-oncotic properties.37 Therefore, prolonged human albumin administration to patients with advanced cirrhosis may restore not only its quantitative but also qualitative defects.37

Increase plasma volume

Because of its high plasma concentration, high molecular weight, negative net charge, and prolonged half-life, albumin is a powerful plasma expander. Indeed, the well-established indications to the use of albumin in patients with cirrhosis pertain to conditions characterized by an acute worsening of effective volemia. However, the albumin dosage employed in long-term treatment would hardly lead to a substantial and sustained plasma volume expansion. Even though plasma expansion cannot be disregarded, other mechanisms likely play a pre-eminent role in promoting the beneficial effects of long-term albumin administration.

Improve the nutritional status

Malnutrition is a severe complication of advanced cirrhosis that entails a poor prognosis.38,39 Therefore, a means able to improve malnutrition would be welcomed, as available treatments often fail. Unfortunately, we have no evidence that long-term albumin administration succeeds in improving the patient’s nutritional status.

Go to section:

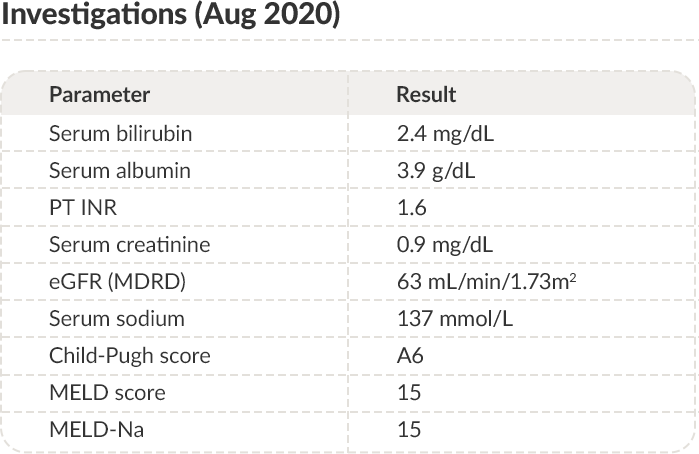

APR 2019-

AUG2020

Clinical results with long-term human albumin administration

Albumin treatment was discontinued at the end of August 2020.

PT: Prothrombin time; INR: International normalized ratio; eGFR: Estimated glomerular filtration rate; MDRD: Modification of diet in renal disease;

MELD: Model for end-stage liver disease.

Trends in serum albumin

Go to section:

Trends in serum albumin

NASH: Non-alcoholic steatohepatitis; HE: Hepatic encephalopathy

Go to section:

What is the importance of assessment of on-treatment

serum albumin concentration during long-term human

albumin treatment?

No relevance

There is evidence that achievement of target serum albumin concentration during long-term human albumin administration is closely related to treatment outcomes.40,41 A different answer is appropriate.

It influences the outcomes

Right answer!

There is evidence that achievement of target serum albumin concentration during long-term human albumin administration is closely related to treatment outcomes.40,41 Two clinical trials recently assessed the effects of long-term albumin administration in patients with cirrhosis and ascites and reported different results.30,42

In the ANSWER study, albumin administration led to better control of ascites, reduced incidence of complications of cirrhosis, and improved patient survival.30 On the contrary, no effect on either the incidence of complications or survival emerged from the MACHT trial.42 The main differences between these trials were related to the dosage and administration schedule of human albumin. The median duration of albumin treatment exceeded one year in the ANSWER study, while it lasted about two months in the MACHT trial due to a high rate of liver transplantation. Furthermore, the administered dosage of albumin in the MACHT trial was approximately half the dosage employed in the ANSWER trial (40 g/15 days versus 40 g/week), which also used a loading dosage in the first two weeks (40 g twice a week). As a result, no effect on serum albumin concentration was seen in the former, while a significant increase by 0.7 – 0.8 g/dl occurred within a month in the latter remaining steady subsequently.30,42

A post-hoc analysis of the ANSWER study database fully confirmed that serum albumin concentration reached at month 1 of treatment is closely related to the outcomes (survival and incidence of complications). Interestingly, the survival benefit continued to progress even after reaching the lower normal serum albumin range (3.5 g/dl), as 4 g/dl were associated with the best outcomes.41

In conclusion, the amount of human albumin administered, and the serum albumin concentration reached by treatment are relevant. Evidence supporting this statement also emerged from another study showing that the absolute increase of serum albumin concentration in patients with baseline hypoalbuminemia was significantly higher in patients receiving 1.5 g/kg/BW per week than in those who received 1 g/Kg/BW every two weeks.

It is relevant that the beneficial effects of albumin administration on effective volemia, pro-inflammatory cytokines, and left ventricular function only occurred with the high dose of albumin.40 Notably, the median serum albumin concentration reached by the high albumin dose was 3.9 g/dl, which is very close to the value

(4 g/dl) associated with the best outcomes in the ANSWER study.

It is relevant to prevent volume overload

In the ANSWER study, 218 patients with cirrhosis and ascites requiring diuretic treatment received long-term human albumin administration.30,41 Signs or symptoms of fluid overload were not seen in any patient. It is very likely that the relatively low amount of albumin given, and the frequency of administration were such to prevent fluid overload.

In any case, volume overload is revealed by physical examination and instrumental signs (chest X-ray; central venous pressure measurement), but not serum albumin concentration.

It is only relevant in patients with

severe baseline hypoalbuminemia

Serum albumin concentration achieved by long-term administration is relevant in all patients with cirrhosis and uncomplicated ascites undergoing this treatment. The results of the ANSWER trial and the post-hoc study dedicated to this matter show that on-treatment serum albumin concentration predicts the outcomes irrespective of the baseline serum albumin level.30,41

Go to section:

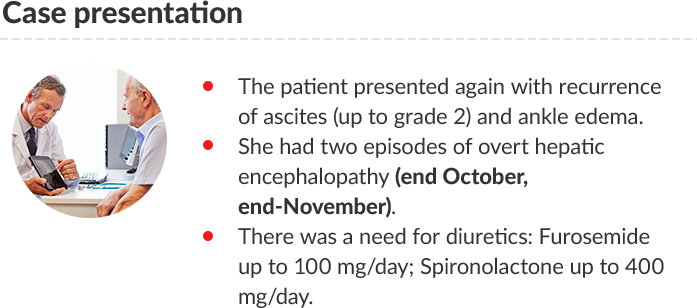

SEP-NOV

2020

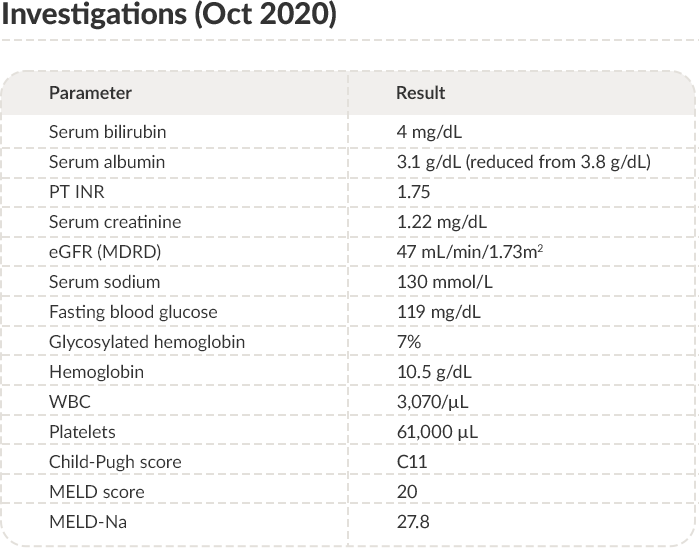

FIFTH presentation & investigations

PT: Prothrombin time; INR: International normalized ratio; eGFR: Estimated glomerular filtration rate; MDRD: Modification of diet in renal disease;

WBC: White blood cells; MELD: Model for end-stage liver disease.

Trends in serum albumin

Go to section:

Trends in serum albumin

NASH: Non-alcoholic steatohepatitis; HE: Hepatic encephalopathy

Go to section:

How would you manage this patient?

Increase the diuretic dosage

The diuretic dosage reached in this case was close to the upper limit recommended by current guidelines. Moreover, reduced glomerular filtration rate, hyponatremia, and episodic overt hepatic encephalopathy represent risk factors for diuretic-induced side effects.12,13 Therefore, a further increase in diuretic dosage does not appear to be an appropriate choice.

TIPS insertion

Child-Pugh score C11 and recurrent overt hepatic encephalopathy advise against transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt insertion. Other choices are preferable.12,13

Striking reduction in dietary sodium amount

Although controlled sodium intake would be advisable, diets with very low sodium content (< 40 mmol/day) in patients with reduced glomerular filtration rate and hyponatremia enhance the risk for further worsening.13,39 Moreover, these diets are unpalatable leading to scarce compliance or reduced calorie intake. The latter is relevant in patients with advanced cirrhosis who are at risk for malnutrition.43

Restart long-term human albumin

administration

Right answer!

Several aspects presented by the patient at this time of her clinical history militate against increasing the diuretic dosage (high diuretic dosage, reduced glomerular filtration rate, hyponatremia), inserting a transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (Child-Pugh score, recurrent overt hepatic encephalopathy), or prescribing a diet providing very little sodium content.

Considering the evidence provided by the ANSWER study,30,44 and the beneficial effects observed during the previous course of long-term human albumin therapy in this patient, it sounds reasonable to re-start this form of treatment. For the time being, such a decision descends from clinical judgment, but formal recognition of long-term albumin administration benefits by international guidelines and regulatory authorities will hopefully take place soon.

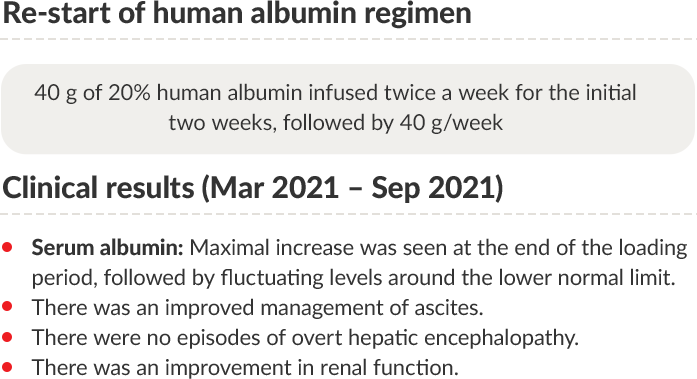

Go to section:

DEC 2020-

SEP2021

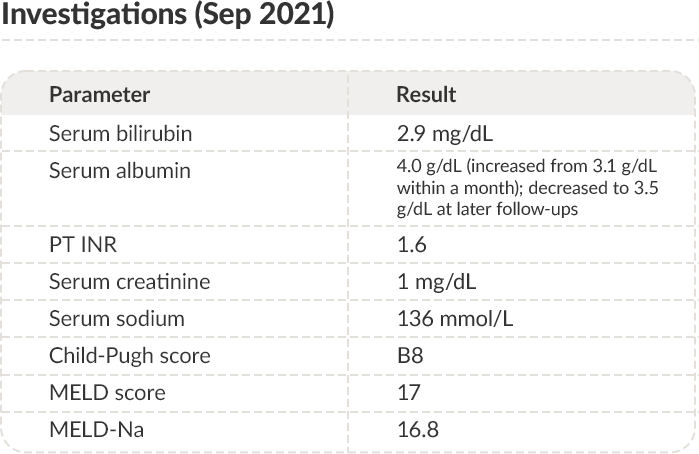

Clinical results after restarting human albumin administration

PT: Prothrombin time; INR: International normalized ratio; MELD: Model for end-stage liver disease.

Go to section:

Case Summary

A 62-year-old woman with diabetes and class

II obesity was diagnosed with NASH-related

cirrhosis with episodic hepatic

encephalopathy

Management

She presented with grade 2 ascites and ankle

edema with prior episodes of overt hepatic

encephalopathy (grade II) in Sep 2017 and May

2018; imaging investigations revealed

adenocarcinoma (T1, N0, M0)

Management & follow-up

Investigations in Feb 2019

Management

Readmission due to overt hepatic

encephalopathy (grade II–III)

Diagnosis: Spontaneous bacterial peritonitis

Management:

Readmission due to persistent ascites grade

2–3, fluctuating hepatic encephalopathy (I–II)

and edema requiring diuretics

Management

Clinical results with long-term

human albumin

Albumin therapy was discontinued

at the end of Aug 2020.

Recurrence of ascites (grade 2) with ankle

edema and two episodes of overt hepatic

encephalopathy (Oct & Nov).

Investigations in Oct 2020:

Management

Clinical results after restarting

human albumin

NASH: Non-alcoholic steatohepatitis; eGFR: Estimated glomerular filtration rate; AKI: Acute kidney injury

Summary of trends in serum albumin

Go to section:

Summary of trends in serum albumin

NASH: Non-alcoholic steatohepatitis; HE: Hepatic encephalopathy

Go to section:

How would you continue to manage this patient?

Continue long-term albumin administration

Right answer!

By Sep 2021, the patient had received albumin for the last 9 months. In the ANSWER study, the treatment with albumin lasted up to 18 months.30 Therefore, albumin treatment may continue even though rules guiding long-term therapy duration are not settled yet. The reasons that may favor this choice: successful control of ascites, no episodes of overt hepatic encephalopathy or bacterial infections in the last nine months, improvement of prognostic scores, improvement of renal function, and resolution of hyponatremia.

Notably, serum albumin concentration increased by 0.9 g/dL (from 3.1 to 4 g/dL) after the loading dose period, then fluctuated around 3.5 g/dL. From the perspective of individualized therapy, increasing the weekly albumin dose may be warranted trying to reach the optimal albumin serum level of 4 g/dL. However, the post-hoc analysis of the ANSWER study database showed that even when on-treatment serum albumin concentration did not reach the lower limit of 3.5 g/dL, patients had a survival benefit compared to those who received the standard medical treatment.41

Stop long-term albumin administration

The rules for discontinuation of long-term human albumin administration are not yet established. In the ANSWER study, treatment with albumin lasted up to 18 months.30 The current clinical success (successful control of ascites, reduction in the number of episodes of hepatic encephalopathy or bacterial infections in the last 9 months, improvement of prognostic scores) and laboratory features (improvement of renal function, resolution of hyponatremia) were satisfactory. Stopping albumin administration may lead to the deterioration of the patient condition, as it happened after discontinuation of the first-course of albumin therapy.

TIPS insertion

By Sep 2021, ascites was well controlled by the diuretic

treatment. If patient condition does not change, there is no indication for TIPS insertion.

Increase the dosage of diuretics

By Sep 2021, the patient presented with grade 1 ascites. Long-term human albumin treatment had allowed a substantial reduction of the diuretic dosage administered before the start of long-term human albumin treatment. If albumin treatment continues, there is no reason for increasing the diuretic dosage.

Go to section:

Key clinical practice pearls

Go to section:

Reference list

Go to section:

Reference list

Go to section:

Thank you